Cultural Geography

Aldrich, Robert, The Seduction of the Mediterranean. Writing, Art and Homosexual Fantasy, London/New York: Routledge, 1993.

Bell, David and Gill Valentine (eds), Mapping Desire. Geographies of Sexualities, London/New York: Routledge, 1995.

Betsky, Aaron, Queer Space. Architecture and Same-Sex Desire, NY: Morrow 1997.

Bleys, Rudi, The Geography of Perversion. Male-to-Male Sexual Behaviour outside the West and the Ethnographic Imagination 1750-1918. London: Cassell, 1996.

Hallam, Paul, The Book of Sodom, New York/London: Verso, 1993.

Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette and Yolanda Retter (eds), Queers in Space. Communities/Public Places/Sites of Resistance, Seattle: Bay Press, 1997.

Keeley, Edmund, Cavafy's Alexandria. Study of a Myth in Progress, Cambridge Ma: Harvard University Press, 1976.

The location of cultural geography is where culture meets space. In the end, this is any place, confirming for same-sex desires the slogan "we are queer, we are everywhere". When we think of gay spaces, most often neighbourhoods are meant where gay men live, heavy cruising goes on or gay bars are concentrated. Such places are alternately called getto's or communities. But the queer presence goes much farther. Gay culture exists on all places where gay traces have been left, and often extinguished once more. It includes everything from bedrooms and monuments to tales, kisses, clothing, body language, music and dreams.

The essential introductory anthology Mapping Desire edited by Bell and Valentine gives a broad range of topics that pertain to gay cultural geography. The first section "cartographies/identities" deals with various gender performances and public discourses on bisexuality and on "moffies, kaffirs and perverts" in South-Africa. The following part "sexualised spaces: global/local" discusses the home, the flaneur, gay fantasy islands and offers "a framework for analysis" of sexuality in urban space. The anthology continues with "sexualised spaces: local/global" on local situations of lesbians in Park Slope, Brooklyn; gays and lesbians in North-Dakota and the traditional Red-Light District in Alicante, Spain. HIV and safe sex, Jamaica and queer politics are the topic of the last series of five articles on "sites of resistance". There are long introductory and concluding essays.

The second important and well illustrated anthology in this field, Queers in Space, edited by Ingram, Bouthillette and Retter, has been summarized under the caption "urban history". It offers a broad overview of the visible and invisible places of queer culture in its gay, lesbian and bisexual manifestations. It includes discussions of physical, political and mental maps and intertwines the literary and social aspects of queer space production. Discussed cities range from New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Vancouver to Williamstown and Mexico while the work of such diverse authors like Pat Califia, Samuel Delany and Gertrude Stein surfaces in the collection. Beaches, parks, bars and streets are mapped for their queer functions. The activism of Dangerous Bedfellows and Lesbian Avengers is discussed. It is the richest overview of the field at this point, although it relies regrettably too heavily on North-American examples.

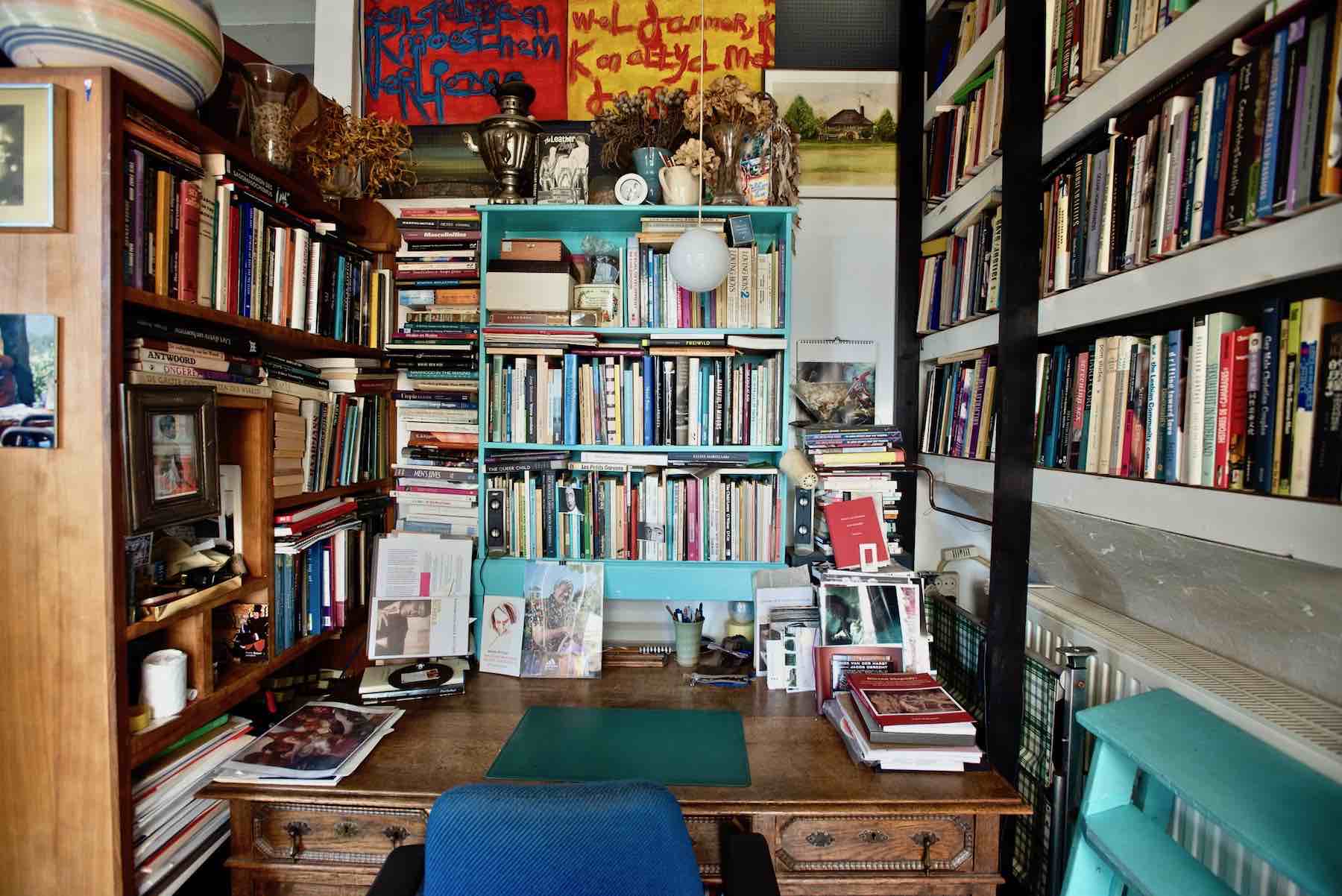

Betsky's book on queer architecture is a nicely illustrated coffeetable book that offers easy reading. It starts with the very true and important claim: "By its very nature, queer space is something that is not built, only implied, and usually invisible". This invisibility makes one wonder how most young queers nevertheless succeed in finding their way to the gay world. There is a strong focus in the book on gay architects, private homes and interior design, missing in most other mentioned studies, and again on artistic and literary queerness. The final chapter is about the "void" that AIDS created in gay life, and the new queer spaces and cultures that reemerged from this void.

The topic of the "wandering gay" is discussed in two books. Aldrich's book offers an overview of European gay travel literature focussing on the south-bound desire for the Mediterrenean where same-sex pleasures should have been more readily available than in Northwestern Europe. Bleys analyzes how "native" forms of same-sex behavior and desire were described and later incorporated in western discourses of homosexuality. These two excellent books cover mostly pre-Second World War developments. The interaction between desire, repression and migration deserves more attention in a globalizing world where sexual attraction often crosses borders of nations and ethnicities. Gay culture, which has become remarkably international, has kept however many local forms and flavors.

Interestingly, many names for (homo)sexual activities refer to geography: sodomy being the most famous, but also buggery (Bulgaria), the French, German, Turkish and other vices, Greek love, "florenzen" (German for sodomy). "French" is an often used adjective to indicate eroticism, as in combinatons with kissing and novel. In western cultures and elsewhere, it is often "the other" who is accused of committing sodomy. The slander is often reciprocated, as between France and Germany, between nazism, communism and capitalism, catholics and protestants, muslims and christians.

Paul Hallam has collected many texts on Sodom and sodomy from past and present in a readable anthology. It includes quotations from the Bible, Voltaire, the Marquis de Sade, John Milton, Marcel Proust, Robert Duncan, Aldo Busi and many others, from sermons, theological, legal and medical texts. Many other books are available on the history of sodomy and Sodom, the mythical city on the bottom of the Dead Sea of which no potsherd has ever been recovered. God destroyed Sodom and the other "cities of the plain" because of the sins of their inhabitants. The interpretation that this sin should be homosexual behavior, is nowadays replaced by another that they sinned against the laws of hospitality. Thus sodomy becomes a double gay myth with a lost city and changing interpretations of a mysterious text.

Myths are produced around certain locations, and Sodom has offered the longest standing and most important gay myth. Antinopolis, the city that the Roman emperor Hadrian built in honor of his lost lover on the banks of the Nile, disappeared and was lost to the gay imagination. Later, other cities have produced major gay myths, like Florence, Paris, Berlin, Tanger, San Francisco, Amsterdam. A rich literature is available to contribute to their gay cultural geography, most explicitly in the form of cultural guides.

Keeley's book on Cavafy's Alexandria is a fine study concentrating on one poet and his city that symbolized for him the Greek tradition from ancient to his own times. As gay themes run abundantly both through Greek history and the life of Cavafy in Alexandria, they are well represented in his poetry and Keeley's book. Armistead Maupin's novels on San Francisco and Charles Kaiser's "The Gay Metropolis" (1997) on New York are comparable, contemporary contributions to gay cultural geography. But the most important places of queer mythology are nowadays the media, especially film and television.